Basics of Electrochemical Double Layer Models

Overview

"Opposites Attract." - Unknown?

This is a famous quote used in magnets, romance, and even for the topic at hand, electrochemical double layers. Here, we will go over the classical Electrochemical Double Layer models and some brief derivations of how these models were conceived. Since I am glossing over a lot of key math principles, this post is more as an introduction to the vocabulary and fundamental principles of the electrode-electrolyte interface. I will suggest further reading or you can just contact me.

1. The dilemma: how to visualize electrocatalytic interfaces?

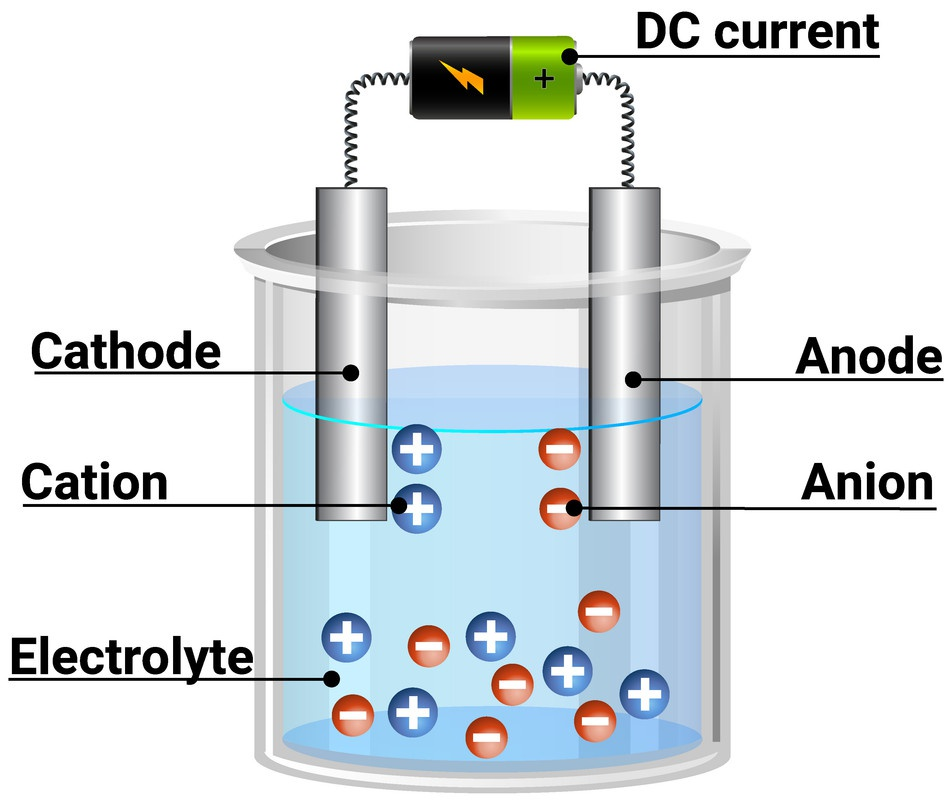

Electrochemical cells are fundamental in electrochemistry. As shown below, these cells (galvanic or electrolytic) have two half cells that respectively mediate the oxidation and reduction reaction. These are all connected through a closed loop between the two cells, circuits, and the electrolyte that mediate charge transfer within the whole system.

This seems elementary but the dilemma at hand is where are the ions at each respectively electrode. It is important to have an understanding of the distribution of ions to design better electrocatalytic systems and understand the fundamental phenomena occurring at these interfaces (ex: cation effects in CO\(_2\) reduction). We know that the charged ions are attracted to oppositely charged electrode (ex: cations attract to the cathode) but where are they distributed? Additionally, how does the distribution differ at the bulk solution electrolyte far away from the electrode versus the electrode-electrolyte interface? What does this interface that is so-called the electrochemical double layer (EDL) look like? Currently, one must recognize that sadly the distribution of ions and the properties of the EDL are quite unknown. However, three classical electrochemical double layer models were developed to answer these questions and provide a foundation of what an “ideal” electrode-electrolyte interface may look like and provide the language to communicate regarding the EDL.

2. Models of the Electrochemical Double Layer

Here, I will go over three classical electrochemical double layer models in order of increasing complexities.

- Helmholtz

- Gouy-Chapman

- Gouy-Chapman-Stern

2.1 Helmholtz

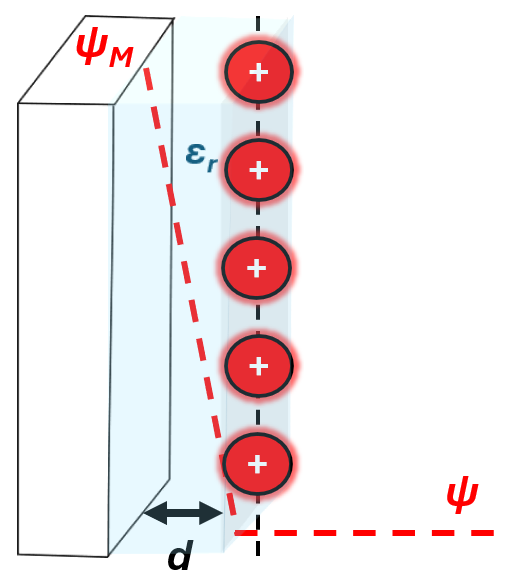

The Helmholtz model in my mind is a basically a sandwich. Your two pieces of bread are the charged metal and the oppositely-charged ions that are electrostatically attracted. Then, a dielectric medium (ex: solvent or vacuum) are trapped between these two “pieces of bread”. This is basically the Helmholtz model.

Hermann von Helmholtz recognized that an interface is formed when two phases (the charged solid electrode and the electrolyte) come in contact due to their opposite polarity. The model is analogous to a parallel plate capacitor, where two layers of opposite charges form the interface, representing the charged electrode and the oppositely charge ions (counterions) as shown below.

Assumptions

The model is a compact and rigid, where the counter ions are distributed as a planar parallel plate consistent of the charge opposite to the electrode. This assumes that the electric field, \(E\) is constant between the metal and the countercharge, which is written as:

\[\frac{d\Psi}{dx} = -E = -\frac{\Psi_m-\Psi_{bulk}}{d}\]The distance where the counter charge planar approaches the surface is defined by \(d\). Within \(d\), the potential, \(\Psi\) , decreases linearly from the potential of the metal, \(\psi_M\), to the potential of the bulk solution or the countercharge, \(\Psi_{bulk}\) . This is due to the planar nature of the countercharges and that the Helmholtz models assumes that these countercharges electrostatically screens the potential. As you can see, the electric field is both dependent on the separation between the countercharge and the metal and a constant value in the Helmholtz model.

As mentioned before, the Helmholtz model can be described by a parallel plate capacitator. The capacitance describes the charge across a potential difference as shown as:

\[\frac{C}{A}=\frac{\Delta q}{\Delta\Psi}\]The charge is related to the charge density on the electrode as:

\[\Delta q= \sigma A\]Using Gauss’ law, the charge density is also related to the electric field, which is constant, as:

\[\sigma = \epsilon_r \epsilon_0 E\]where the relative permittivity (dielectric constant) of the Helmholtz EDL is \(\epsilon_r\), and the vacuum permittivity is \(\epsilon_0\). These equations can be combined to show that the capacitance of the EDL is potential-independent as a consequence of the constant electric field (or linear potential drop).

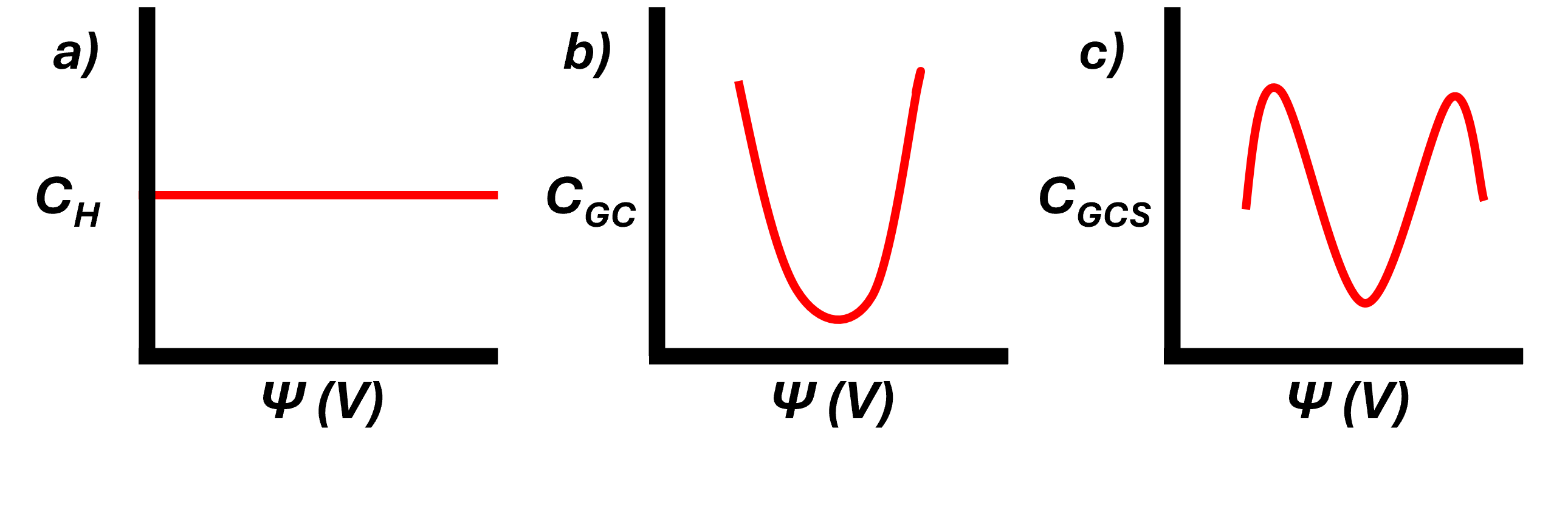

\[\frac{C}{A}=\frac{\Delta q}{\Delta\Psi}=\frac{\sigma A}{\Delta\Psi}=\frac{\epsilon_r \epsilon_0 E}{\Delta\Psi}=\frac{\epsilon_r \epsilon_0 \frac{\Delta \Psi}{d}}{\Delta\Psi}\] \[\frac{C}{A} = \frac{\epsilon_r \epsilon_0}{d}\]This shows that the capacitance of the EDL described by the Helmholtz Model is only dependent on the dielectric constant and separation of charge. The Helmholtz model provides a simple framework in understanding electric fields and capacitance within the interface for approximately a highly concentrated electrolyte.

Limitations

While the Helmholtz model is simple, it ignores a few key aspects:

- Diffusion/mixing of ions in solution as the ions are all presumed to be present as a parallel plane

- Any adsorption on the surface (ions, reactants, etc)

- Solvent Interactions with the electrode since the solvent is really approximated as a continuum view by the constant dielectric constant

2.2 Gouy-Chapman Model

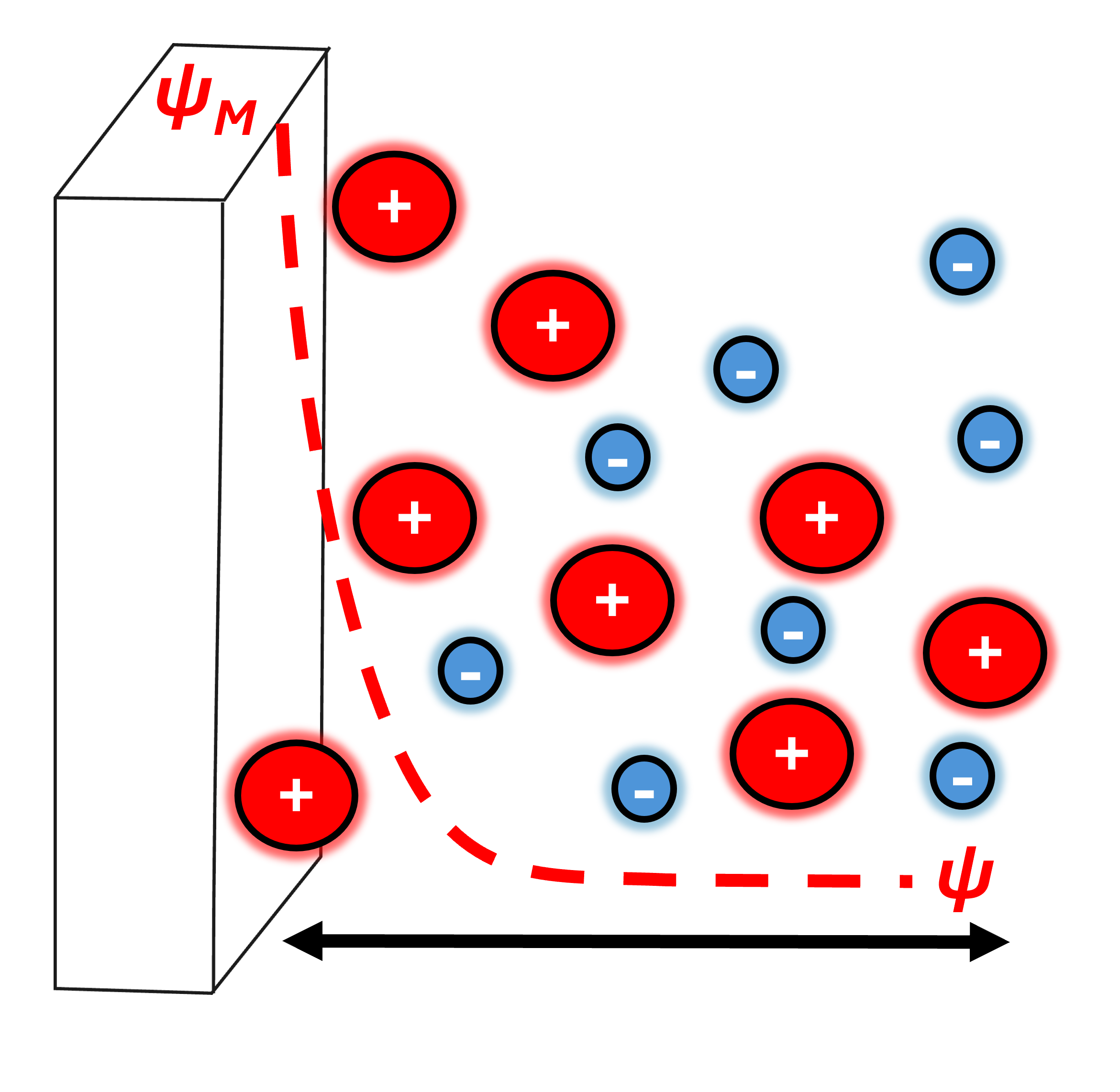

In real life, the capacitance is both dependent on the potential and the electrolyte composition. Louis Georges Gouy and David Leonard Chapman introduced a diffuse model of the double-layer where the charge distribution of ions is dependent on the distance away from the surface as shown below.

Here, all ions are allowed to move in solution based on electrostatic interactions competiting with the motions described by Brownian. In other words, the electrostatic attraction between opposite charges is in competition with the thermal motions based on entropy. This model is valid for dilute solutions and minimal polarization at the electrode.

Assumptions

The model utilizes Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics to approximate the distribution of ions, resulting in the applied potential to decrease exponentially from the surface to the bulk solution. The derivation is a bit complicated as the Poisson-Boltzmann differential equations must be solved. However, I will highlight key equations.

First, the distribution of ions \(n_i\) are described by a Boltzmann distribution as:

\[n_i = n_i^0 exp(\frac{-z_ie\Psi}{kT})\]which approximates the distribution by thermal motion as \(n_i^0\) is the bulk concentration of the ion, e is the unit charge, \(z_i\) is the charge of the ion, k is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the absolute temperature.

Now the next parts require solving a boundary condition problem and a set of differential equations. To save everyone the torture from these long derivations, I will provide the next few key equations. Please refer to the first reading I reference later but here are two key equations.

First, the applied potential can be solved based on the Gouy-Chapman model as:

\[\Psi(x)=\Psi_{metal} exp^{-k_{GC}x}\]which shows how the potential drop relative to the metal exponentially decays as the distance becomes larger away from the surface. Increasing the distance away from the surface induces a larger potential drop. Note that \(k_{GC}\) here is the reciprocal of the thickness of the double layer also described as the Debye length \(\lambda_d\). Larger Debye lengths lead to “less steep” of a potential drop.

\[\lambda_d = \frac{1}{k_{GC}} = ({\frac{\epsilon_r\epsilon_0k_B T}{2\sum z_i^2 e^2 \rho}})^{\frac{1}{2}}\]where \(\rho\) is the ion concentration, e is the elementary charge of the electron, and z\(_i\) is the charge of the ion. Larger Debye lengths lead to a “less steep” of a potential drop.

The electric field is taken as the negative gradient of the potential as shown before as:

\[E(x)=-\nabla \Psi(x)\]Lastly, the differential capacitance is described by a nasty equation as:

\[C_{GC}=(\frac{2z^2e^2n_i^0\epsilon_r\epsilon_0}{kT})^{\frac{1}{2}} cosh(\frac{z\epsilon\Psi_{Metal}}{2kT})\]where basically the main take away is the capacitance is now dependent on the applied potential at the metal. I will later show that the capacitance shows a parabolic dependence on the applied potential.

I have provided a link to a Google Colab notebook that models both the potential and capacitance profile as you vary the parameters in a Gouy-Chapman Model.

Limitations

The Gouy-Chapman model has several following limitations:

- It fails for electrolyte’s with high concentrations and metals with large polarization.

- The model is only valid for potential differences close to zero and very dilute solutions.

- Ions are point charges in thermodynamic equilibrium

- This overestimates the distribution of ions to be too concentrated once the surface is polarized sufficiently

- The model is mean field so no specific interactions

2.3 Gouy-Chapman-Stern Model

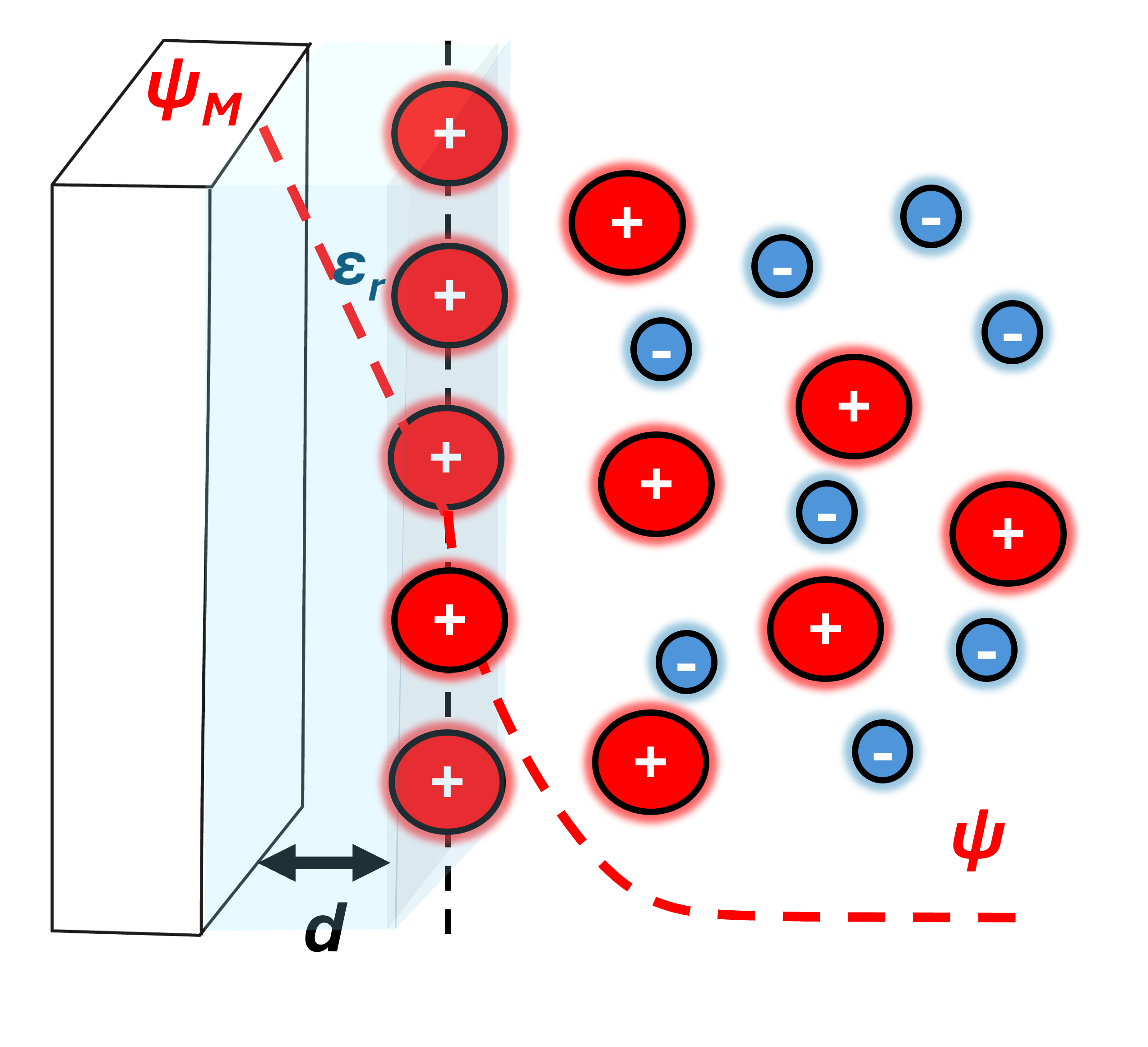

Addressing these concerns, Otto Stern simply just combined the two models together. The Stern or “Helmholtz Layer” is simply suggesting ion’s have a closest approach (based on radius) and outside of this region is the diffuse layer from the Gouy-Chapman model.

Assumptions

Ions are assumed to have finite sizes or closest approach and are not point charges within distance d. This is the Stern layer. The ions outside of the stern layer and in the now diffuse layer are point charges. There are two potential drops. One is the linear potential drop in the Stern layer. The latter is the exponential decay described by the Gouy-Chapman model.

The major math conclusion from this model is the fact that the capacitance of the entire double-layer can be described by a two capacitors in series for the Stern and Gouy-Chapman portions of the model. This is given as:

\[\frac{1}{C}=\frac{1}{C_{Stern}}+\frac{1}{C_{GC}}\] \[C=\frac{C_{Stern}C_{GC}}{C_{Stern}+C_{GC}}\]There are two cases that this model shows. First, if the concentration is high, the double layer is fixed and is represented as the Stern layer. Second, if the concentration is dilute, the double layer is more Gouy-Chapman like. This produces the famous “double hump capacitance” for a ideal polarizable surface in contact with a non-interacting electrolyte.

3. Outlook

A summary of the three classical model are shown in the following.

Here we can see how the capacitance can very between different models of the EDL. Despite the GCS seeming the most reasonable model, even this model lacks agreement experimentally. It does not consider adsorption and chemical reactions at the surface, reactive surfaces with complicated active sites, specific solvent interactions, anisotropic distributions between the ions and solvent outside of the simple mean field approaches, and more. I have provided further reading to touch on these topics. However, the basis of this post is to introduce these models and the intrinsic differences between these models.

As always, feel free to reach out if you have any questions and recommendations.

Future Works for myself

- Provide a Python script to model the distribution of ions and fields for each model as you change the parameters within the models (dielectric constant, distance, etc)

4. References

Basics of EDL models

- Classic Models of the interface between an electrode and an electrolyte

- Basic Theories of EDL models